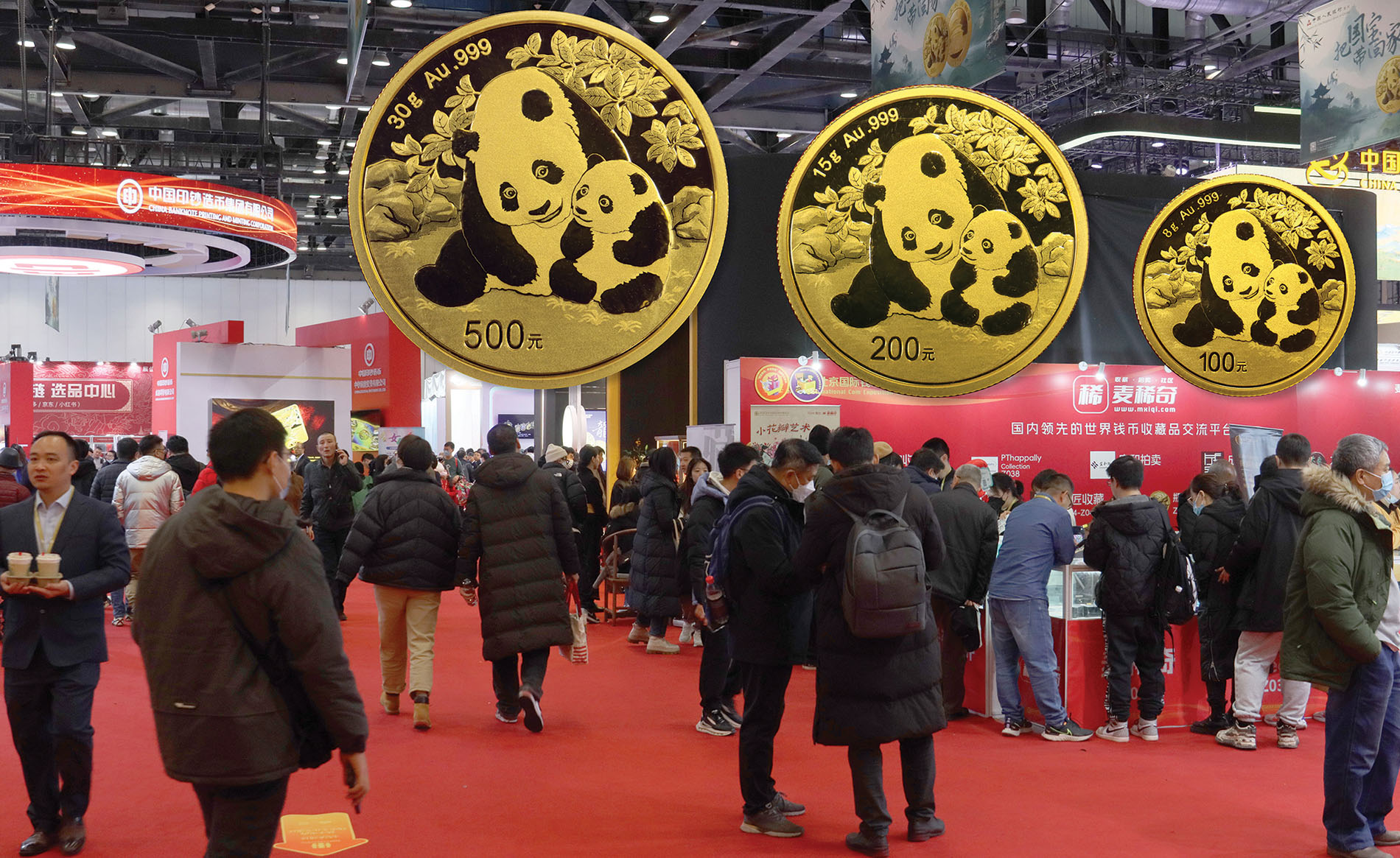

In unison, six dancers precisely turn a quarter circle. Then, one by one, the women slowly rotate back as their left arms sweep upward toward the high ceiling of the China National Convention Center. Their blue, green, and ochre-colored costumes swirl through the air. Behind the performers, a large screen displays images of mountains and valleys, painted in colors that match not only the costumes, but also the artwork on the four coins in the new 2024 Famous Ancient Chinese Painting series. The crowd grows larger and larger, a hundred phones held high to record the event. Above the din rises a traditional Chinese melody plucked on a zither.

“Are you going to the Panda Launch?” a friend yells to me from three feet away. The launch will mark the official release of the 2024 Panda coins.

“Do I need a ticket?”

“No, just be there.”

It is December 1, 2023, and we are standing on the floor of the 2023 Beijing International Coin Expo. This is the first in-person BICE since 2019. The building is filled with people excited by coins, banknotes, and the like. They hurry in past the showrooms hosted by institutions like China Minsheng Bank and the Agricultural Bank of China. These offer gold and silver bars, medallions, and cultural items like teapots for sale. Panda coins are a popular choice among gold buyers. These luxury bank “booths” are practically flats, large enough for clients to sit inside, drink tea and watch fairgoers stream by.

Down every aisle there are display areas for all types of numismatic-related companies that make coin and currency boxes and albums or that sell jewelry and precious metal objects of all sorts. One piece that catches my eye is a silver abacus pin that also holds a three-gram gold Panda coin. This is the work of Miss Tong Fang, the designer of the 2023 Panda coin, as well as many other Chinese coins. It is my pick as the prettiest gift of the show. Further on, a long line forms at the PCGS area, where people wait to play a coin-grading game in which a handsome, large canvas tote bag is the prize.

A short distance to the left of the dance stage, China Gold Coin displays a rare 1991 five-kilogram gold Panda coin along with other modern rarities. (Note: this particular coin puzzles me. There is supposed to be a serial number from 1-10 stamped on the rim. On this example, a steel band wrapped around the edge makes it impossible to see the rim. One coin was retained at the Shenyang Mint, where the mintage was struck. Is this that coin or a sample? When asked, the workers at the booth don’t know. Just across the walkway from the China Gold Coin exhibit, a spectacular complete collection of five-ounce Panda gold coins is on display. It is presented by the Yong Yin Coin Museum in Nanjing, a spot that belongs on every numismatic tourist’s itinerary.

Among the most popular attractions are the government mints like the Shenyang, Shanghai, and Shenzhen Guobao Mints. Mints that are less well known outside the country, like the Chengdu Mint and Zhongchao Guanghua Mint, also are busy. Foreign mints are popular, especially the Perth Mint and the French mint, Monnaie de Paris (which served hors d’oeuvres at lunch time the first day of the show). Foreign dealers like MDM from Germany and Panda America also get attention. Neil Vance of the Perth Mint receives an award from the show for his many years of contributing to the growth of Chinese Numismatics. Afterward, he tells me that the Perth Mint has always greatly valued its relationship with China and that he wouldn’t miss this show. Indeed, the Perth Mint struck platinum coins for China back in the 1990s.

The Panda Launch is held at the Intercontinental Hotel that is across the street from BICE but connected by a bridge. I hurry across it and arrive just in time to catch the start of the ceremony. Miss Huang Qin, the coin designer of the 2024 Panda coins, presents a detailed discussion of the history of the Panda series and the design process for the newest coins. Following her, half a dozen designers and engravers of previous coins are called on stage to receive awards.

One very special aspect of BICE is the opportunity it affords to meet the people who shape China’s numismatic program. For instance, at the Shanghai Mint booth, Mr. Luo Yonhgui — the designer of more than 100 Chinese coins — explains the technical processes of coin minting and design to a group of rapt collectors huddled around him. Most of the top coin designers in China make appearances — Mr. Zhu Xhihua, Ms. Tong Fang, Ms. Chang Huan, Mr. Liao Bo, Ms. Huang Qin, and many others — as well as top mint executives.

BICE, though, is much more than a numismatic trading venue. It has become an educational and cultural event in its own right. This places it among the world’s elite coin shows like the World Money Fair (held each winter in Berlin) and the American Numismatic Association’s World’s Fair of Money (United States). The basic trading show format was established centuries ago: it lasts for a limited number of days, exhibitors and visitors travel to reach it, and there is active trading. One medieval trade fair was described like this, “By river, by road, afoot through the forest traders of all kind began to make their way to (the town)… Once a year, they came to buy the fine wines, the luxury cloths, the gold and silver work — all the treasures that appeared for the fair and vanished three days later.”

Temporary festivals were a novelty in Medieval Europe. Unlike permanent markets, or bazaars, which existed since ancient times, trade fairs were short, intense, and reached an audience outside major cities. An important side effect was that they allowed common people to earn cash. That sparked economic growth and development that was stifled under the feudal system. The roving merchants further undermined feudalism with their support for strong central governments that made travel safer. The first recorded trade fair was held in Frankfurt, Germany, in 1150 A.D. There is no record of any coin traders there (although who can say?), but it was the distant ancestor of all coin shows.

The first Beijing International Coin Expo was held in 1995 and is partly remembered today for its scarce one-ounce silver Panda commemorative coin, of which 18,000 were minted. During its early years, the excitement about the new show was extreme, the atmosphere filled with speculation and feverish trading. The show opened at a time when Chinese coins were rising in prominence internationally and drawing ever more interest at home.

In 2023, while there are many booths along the sides and back of BICE for the retail coin business — and China Gold Coin, itself, has a large retail sales area — a significant part of today’s expo is devoted to information.

One excellent example of this is the exhibit of the China Numismatic Museum. This year it features charms and amulets, not coins, through the country’s history. I stopped by there and met Mr. Lu Xin, who goes by the name Bob and curated the exhibit. As I looked down at one showcase, he explained, “These date from the Han Dynasty, more than 2,000 years ago. Unlike modern lucky charms, in those days most of these were meant to protect against bad luck, not bring good luck. That is what was on people’s minds.”

I look down at a thousand-year-old Song Dynasty (960-1227) piece. It resembles a cash coin with a round hole in the center. Instead of being money, though, with the emperor’s mark on it, the characters form a prayer to eliminate disasters. Another charm from the Liao Dynasty in northern China wishes longevity to its bearer.

Charm designs evolved as Chinese art did. Poetry was the starting point, and some charms even have a poem on one side. Then, as art expanded from poetry and calligraphy to painting, charms became more visually creative, too.

My conversation with Mr. Lu is interrupted by the arrival of two outstanding coin designers who drop in to say hello: Mr. Luo Yong Hui and Miss Jin Yan Xuan of the Shenyang Mint. As everyone talks, several employees of the museum bring out uncut sheets of new souvenir banknotes for us to admire. The subject of the notes is a dragon. Its colors under room light are shades of maroon red and lemon yellow. When an ultraviolet light shines on the note the shape of the dragon instantly glows a stunning golden-yellow.

Coincidentally, a placard posted on the wall relates to the note. “The year 2024 is the Year of the Dragon. The dragon is the only animal in the Chinese calendar with a divine nature. It is both a cultural emblem and the spiritual symbol of the Chinese nation. It bears witness to the formation of the Chinese nation and serves as a bond of affection for the Chinese people… In many artistic works we can see various shapes of the dragon.”

Right below the sign two charms illustrate this, as both are decorated with double dragon designs. One is from the Qing Dynasty and another, well worn, is from the older Five Dynasties (907 to 979 A.D.) era. This was a time of political upheaval and strife when people needed all the good luck they could find. Incidentally, collecting these non-monetary numismatic relics is growing in China.

The 2024 Panda coin series is officially introduced to the world at the Panda Launch ceremony by designer Huang Qin. Courtesy of Peter Anthony.

Although not in this exhibit, the charms call to mind a set of four “Vault Protector” coins struck in 1998. These coins have a round form with a center hole like cash coins but sport a fantasy design that references the Tang Dynasty. In this set is a 2,000 yuan coin that contains one kilogram of pure .999 gold. Apparently 72 were struck, although the planned mintage was 68. The actual mintages of the other three coins are not definitely known, but the 200 yuan one-kilogram silver had a listed mintage of 2,800, the 10 yuan tenth-ounce gold is listed at 60,000 and the 10 yuan one-ounce silver piece had a planned mintage of 100,000.

Late in the day as I leave, a clang-clang-clang sound of metal-on-metal rouses my curiosity. Its source turns out to be the Shanghai Mint exhibit. A man wields a sledgehammer to hand strike souvenir medals for BICE. I chuckle that this antique Western method, in use at the time of the first trade fairs, is being used to turn out keepsakes for a Chinese coin exposition in the 21st century. Then again, it reflects how culture and knowledge spread and of the long history of trade fairs and shows like the Beijing International Coin Expo – and of coin collecting – itself.

Copper & Nickel

Copper & Nickel

Silver Coins

Silver Coins

Gold Coins

Gold Coins

Commemoratives

Commemoratives

Others

Others

Bullion

Bullion

World

World

Coin Market

Coin Market

Auctions

Auctions

Coin Collecting

Coin Collecting

PCGS News

PCGS News